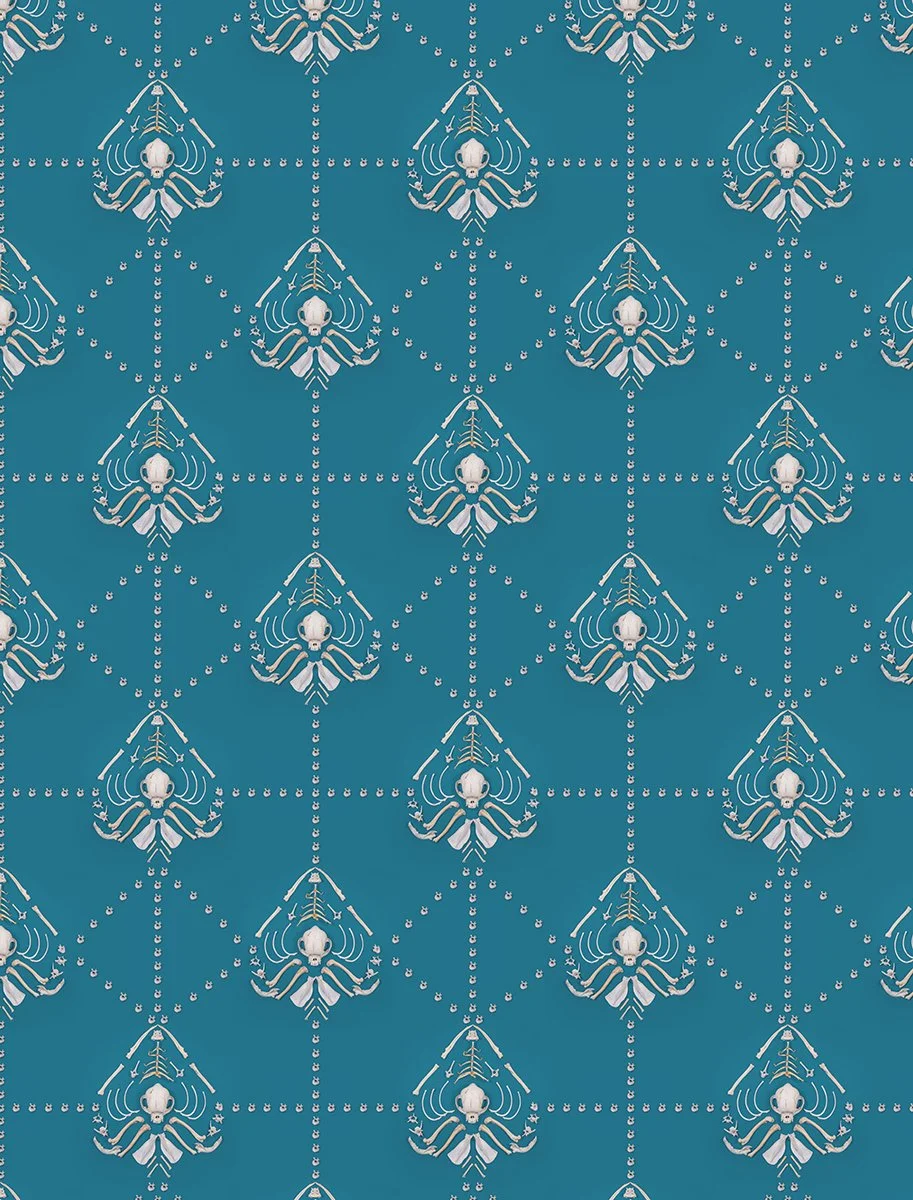

THE WALLPAPER DOGS / DEATH BY BREATH

Parts of a Pug Skeleton, Male (1930). Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Mammalogy Department, Catalog Number LACM 30595. © Sophie Gamand, 2025.

The Wallpaper Dogs / Death by Breath is a visual project that turns brachycephalic dog skeletons—whose deformities are bred for cuteness but can cause immense suffering—into ornate wallpaper patterns. Echoing Victorian arsenic-laced wallpapers, the project questions how far we’ll go for beauty, status, or trend, even when others—animal or human—pay the price.

Created during an art residency at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County in 2025.

“This paper looks to me as if it knew what a vicious influence it had! There is a recurrent spot where the pattern lolls like a broken neck and two bulbous eyes stare at you upside-down.”

— Charlotte Perkins Gilman.

In her book The Yellow Wallpaper (1892), Perkins Gilman describes a woman descending into madness because of her arsenic-laced wallpaper.

If you desired something you knew could cause another’s suffering, would you still want it?

The Wallpaper Dogs / Death by Breath explores the intersection of aesthetics, social status, and suffering through the lens of brachycephalic—or flat-faced—dogs: breeds like Pugs, French Bulldogs, and English Bulldogs, Brussels Griffons or Bull Terriers. These dogs are wildly popular, even as the veterinary community has long warned about their health issues caused by the physical traits we breed into them: breathing difficulties, chronic pain, heat strokes, among other ailments, often leading to short lifespans. These aren’t accidents of nature—they are the result of human preference, bred into the body itself.

And yet, people find these dogs irresistible. In recent years, French Bulldogs have become the number one breed in the United States.

People refuse to listen to veterinarians, and instead believe breeders, blinded by their desire to possess a dog whose esthetic they favor. They get distracted by the adorable faces and ignore that the cute snorting sounds their dog makes are sounds of suffocation.

To tell these dogs’ stories, I thus turn to their skeletons. There lies an undeniable truth. Their deformed skulls, in particular, tell the terrifying and confronting story of these dogs and what we have done to them.

I photographed brachycephalic dog skeletons archived at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles. When arranging their bones into ornate, symmetrical patterns, I prioritized visual appeal over anatomy accuracy. Just like many breeders do, I disrespected the laws of biology and nature, for the sake of design and esthetics.

The skeletons became decorative, consumable.

The suffering became a motif.

Turned wallpapers, these patterns echo the Victorian wallpaper laced with arsenic. The pigments were so vivid and trendy, that by the late 1800s, 80% of wallpapers in the UK contained arsenic. When doctors linked those wallpapers to a series of deaths of children and entire families, they rang the alarm. They were met by apathy from manufacturers, and ridicule from famed designers who called their concern a hoax.

In 1874, health official Robert Clark Kedzie compiled arsenic wallpaper samples into a book, distributed to public libraries to warn the public. He understood that an “enlightened public sentiment” was the only way to put an end to the deathly trend. He wrote: “Whether a poison is administered in ignorance, by carelessness, or by design—the effect of the poison is the same.”

This is true for brachycephalic dogs. Whether their suffering is administered by ignorance of the humans who buy them, through the carelessness of breeders, or by design imposed by breed clubs, the suffering for the dog remains the same.

Brachy dogs were popular during the breeding frenzy of Victorian times. French Bulldogs were manufactured in the late 1800s. There are parallels between brachycephalic dogs and Victorian women: both have had their breathing impaired for fashion and esthetics, kept symbolically weak and controlled. Victorian times celebrated sickly women, romanticizing tuberculosis for example, and saw women’s frail appearance as a symbol of feminine beauty and sensitivity. Similarly, we project personality traits and worth on brachy dogs (such as laziness or stubbornness) although these are usually linked to their physical suffering: a dog who cannot breathe might be reluctant to go on a walk.

The Wallpaper Dogs / Death by Breath is both meant as a visual elegy and a question: When beauty and harm are so tightly woven, can we learn to refuse the cost?

Part of an English Bulldog skeleton, Male (1929). Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Mammalogy Department, Catalog Number LACM 30417. © Sophie Gamand, 2025.